Office Hours

After Hours by Appointment

Contact me to schedule a virtual meeting

Insurance Products Offered

Auto, Homeowners, Condo, Renters, Personal Articles, Business, Life, Health, Pet

Other Products

Banking, Investment Services, Annuities

Would you like to create a personalized quote?

Beau Blessing

Blessing Ins and Fin Scvs Inc

Office Hours

After Hours by Appointment

Address

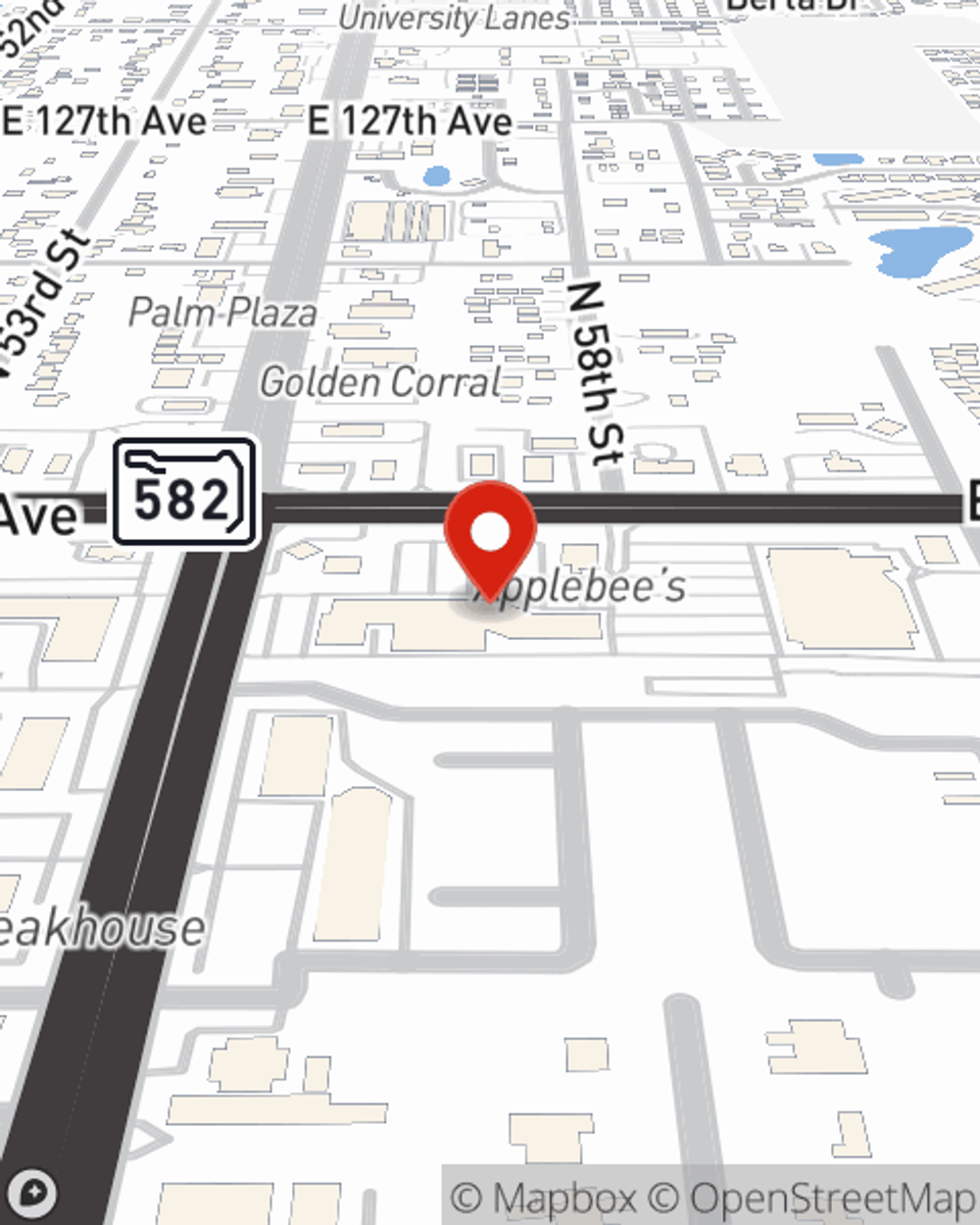

Temple Terrace, FL 33617-2307

Office Hours

After Hours by Appointment

Contact me to schedule a virtual meeting

Insurance Products Offered

Auto, Homeowners, Condo, Renters, Personal Articles, Business, Life, Health, Pet

Other Products

Banking, Investment Services, Annuities

Would you like to create a personalized quote?

Office Info

Office Info

Office Hours

After Hours by Appointment

Contact me to schedule a virtual meeting

Location Details

- Parking: In front of building

-

Phone

(813) 825-2328

Languages

Insurance Products Offered

Auto, Homeowners, Condo, Renters, Personal Articles, Business, Life, Health, Pet

Other Products

Banking, Investment Services, Annuities

Office Info

Office Info

Office Hours

After Hours by Appointment

Contact me to schedule a virtual meeting

Location Details

- Parking: In front of building

-

Phone

(813) 825-2328

Languages

Simple Insights®

Car maintenance tasks you can do yourself

Car maintenance tasks you can do yourself

To combat auto repair costs that keep climbing, some auto maintenance can be done at home. Here are ones that are usually do-it-yourself.

The free Ting offer continues to help keep policyholders safe

The free Ting offer continues to help keep policyholders safe

State Farm is offering free Ting Sensor devices to qualified policyholders in participating states.

Usage-based car insurance for multiple drivers

Usage-based car insurance for multiple drivers

Learn how usage-based auto insurance works with multiple drivers on one policy and how the combined driving habits may affect costs and potential savings.

Social Media

Viewing team member 1 of 4

Irene Days

License #G193997

Viewing team member 2 of 4

Cameron Fischer

Account Manager

License #G240464

Viewing team member 3 of 4

Tonya Wyatte

License #W280586

Viewing team member 4 of 4

Laura Ghezzi

Account Representative

License #G273181

Tampa - FL Full Time

Tampa - FL Full Time

Tampa - FL Full Time

Tampa - FL Full Time

Tampa - FL Full Time

Tampa - FL Full Time

Tampa - FL Part Time

Tampa - FL Full Time